LONG READ: Climate Change and Unity

Introduction

This article will show that the study of climate politics can reveal how successfully different actors have sought to govern the international system. Actors have, in part, successfully done this but there is a long way to go if efforts are to have any lasting and meaningful effect. The article will use neorealism and liberal institutionalism, structured on regime theory, as a handrail to show that actors in the anarchical international system cooperate successfully in order to govern climate change. How and why they are successful will be explored in detail using the two theoretical approaches, each having their strengths and weaknesses to discuss. The finding that although there is much to be done, and in difficult settings, different actors in the international system have successfully sought to govern issues within it — especially so when assessing the question through a liberal institutionalist approach.

Empirical focus will draw information from a summit which was intended to draw members of the international community together to address a particular issue area, climate change. I have chosen this summit because it interests me and is a highly fitting example of how actors are coming together to govern climate change. This exploratory case study is important because it draws out my main line of argument, that governance is successfully happening. Governance is necessary for some issue areas in international politics in order to overcome issues that are of mutual concern. The case study also helps to draw out an important focus point — that varying actors are key to governing issues, top-down state governance is of little effectiveness when it comes to climate change, and ultimately global governance in the contemporary international system. Here, I will show that cooperation by all is key.

The issue

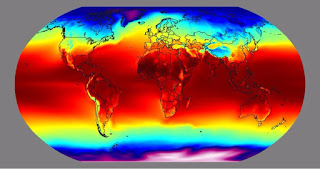

The increase of the global climate temperature average is a phenomenon known as climate change. Human activities can be categorically attributed as the main cause of this. Deforestation, extensive farming and livestock produce, and the vast use of fossil fuels such as gas, oil and coal are human activities that produce large volumes of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. These in turn accumulate in the atmosphere, threatening to irreversibly damage the carefully balanced life across the whole planet. These changes can affect any person, anywhere. Examples of this include excessive rainfall, which causes severe flooding (Vidal, 2015) and less rainfall elsewhere which causes shortages in water supplies (WBG, 2016). Too much heat destroys entire crops (EPA, 2016) and holds potential to spread diseases because the issue sets conditions that ‘…strongly affect water-borne diseases and diseases transmitted through insects, snails or other cold blooded animals’ (WHO, 2016). According to records, ‘…the number of reported weather-related natural disasters has more than tripled since the 1960s. Every year, these disasters result in over 60,000 deaths, mainly in developing countries’ (WHO, 2016). The issue of climate change affects people and animals alike, everywhere. Climate change is ‘…no longer some far-off problem; it is happening here, it is happening now’ (Santiago, 2015). Human activities are the main contributing factor with the issue of climate change, therefore, not only is the issue a political one, it is moreover an inherently human responsibility. As will be discussed below, no actor or state alone can overcome or limit climate change. A formidable institution would be required to begin action against it.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was developed by the international community to address the issue. What led to the creation of the UNFCCC ‘…was the first assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC], released in 1990’ (UNFCCC, n.d. a). This article will explore the IPCC in greater detail below. The UNFCCC is an organisation with 197 Parties from the international sphere and is a treaty which officially recognises climate change. With their ultimate aim being to prevent ‘…“dangerous” human interference with the climate system…’ (UNFCCC, n.d. b), this made way for the Kyoto Protocol, during the second annual Conference of the Parties (COP), in Kyoto.

The Kyoto Protocol is a regime that ‘…committed its Parties by setting internationally binding emission reduction targets’ (UNFCCC, n.d. c), it also placed heavier reduction burdens on states in direct proportion to their level of development. Higher developed states were required to make higher cuts to their GHG emissions because they are not only considered to be the main contributors ‘…since before the industrial revolution’ (Griggs, 2016), but also more able to do so. The reduction of GHGs is inextricably linked to fundamental modern societal life due to the connection with transportation, farming and energy requirements. As such, climate change begins to reveal the requirement for complex forms of governance, to facilitate mitigation and adaptation, in order to address the issue. Unfortunately, although the aim of this regime was with positive intentions, it was ‘…not legally binding as it does not set mandatory limits on greenhouse gas emissions for individual countries and doesn’t contain any enforcement mechanisms’ (WMO, n.d.). The regime therefore lacked adequate supporting legislation. With that, the USA declined to implement the regime because, according to George Bush, it ‘…would have wrecked our economy…’ (NBC, 2005). This absence by a global power undermined the regime and heavily damaged the effectiveness of it. This suggests that a more comprehensive and encompassing agreement may be more widely accepted, adopted and implemented — in an international system identified as anarchical.

Early on in this particular issue area, the effectiveness of climate governance was very limited because the problem was yet to gain enough momentum and acceptance. It required expansion from a state problem to the transnational and global arena, due to the global nature of the challenge. It is possible that the expansion and acknowledgement of the climate issue was proportional to improved climate scientific understanding, chiefly from the findings of a scientific body which will be explored below, in order to connect the issue with transnational politics. This allows for the sub-question of whether climate change governance has gained serious ground in the international sphere, which will be explored by looking at the following case study.

Case Study - Conference of the Parties 21

To specify empirical focus, this article will use the twenty-first session of the Conference of the Parties (COP21) as a case study. Before going into details on how this case study shows successes and strengths for international cooperation it is necessary to go into some detail as to why the COP takes place.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, henceforth IPCC, is the leading international body for the assessment of climate change and it ‘…embodies a unique opportunity to provide rigorous and balanced scientific information to decision-makers because on its scientific and intergovernmental nature’ (Secretariat, 2013). The IPCC has established that GHGs in the atmosphere are directly linked to the global average temperature. According to the IPCC findings, this correlation has been rising steadily since the dawn of the industrial revolution, due to the rise in human generated GHGs. The IPCC understands that burning fossil fuels has produced the main contributing GHG, Carbon Dioxide (IPCC, 2014). The panel released assessment reports on the science of climate change with one categorical conclusion; that the more ‘…human activities disrupt the climate, the greater the risks of severe, pervasive and irreversible impacts for people and ecosystems, and long-lasting changes in all components of the climate system.’ (IPCC, 2014). With these facts in mind, climate change is a burden firmly placed at a transnational scale. As such, forms of cooperation in the international system must be sought if it is to limit the threat that climate change poses to humankind. Ergo, the COP exists today as a measure of tackling this important issue of global mutual concern.

During COP21 in Paris ‘…Parties to the UNFCCC reached a historic agreement to combat climate change and to accelerate and intensify the actions and investments needed for a sustainable low carbon future’ (UNFCCC, n.d. d). This agreement aimed to strengthen actors in the international system in their response to the issue of climate change. The conference itself allows for a focus on the extent and desire for transnational cooperation in the anarchic international system. With that in mind, COP21 went about setting ‘ambitious’ targets. They did so by supporting said targets with funding plans, capacity building frameworks for developing states, and new technology frameworks for all states — all tasks allocated in proportion to individual actors’ abilities (Ségolène, 2016a). Where the Kyoto Protocol had failed, it seems, lessons were learnt and consequently the newly created Paris Agreement addressed said failings. With that; 197 Parties reached acceptance and pledged to ‘…work on nationally determined contributions, transparency, the global stocktake and arrangements for facilitation and compliance’ (Ségolène, 2016b). Figure 1.0 below shows some of the members attempting to squeeze into a single photograph after the agreements (Gosden, 2015). In signing the Agreement, each of the Parties signed consent to be bound by it, which encourages each to take steps to address the problem of climate change. The failure of the Kyoto regime, it is now possible to suggest, laid way for some of the successes experienced at COP21. Laying out regimes is one thing, even from powerful institutions such as the UN, but without the proper framework from which to support it it becomes destined to failure. As a measure of how successfully this actor has sought to govern climate change; COP21 does much to remedy and prevent failure by implementing methodology, technology, capacity building and funding into the agreement.

|

| Fig 1.0 Image: UN Climate Change Conference |

The ultimate success of COP21 and climate governance is yet to be distinguished but this case study shows clear cooperation between international actors in their attempt to address the issue. Actors, in this case 196 states and one institution, the EU, have unquestionably sought to govern the issue. With 197 actors cooperating, the chance has never been greater to successfully govern climate change. Also, giving that those actors would not have agreed to voluntarily commit unless the pledges were permissible, given that the international system is anarchical, the nature of the current level of governance is undoubtedly a sign of success.

All Parties voluntarily committed to the Paris Agreement, as such it is possible to suggest that the Agreement could have been afflicted with a lack of desire from the stakeholders. However, said potential weakness in this case did not present itself and remains merely a thought experiment to show how it could have failed in order to expose the weakness. Strengths for this case study go hand in hand with its success. The 197 Parties under anarchy coming together, effectively communicating, collaborating, cooperating, then agreeing to implement changes to address an area of mutual concern boasts of an important milestone. The focus aspect of COP21 makes way for the wider issue of how anarchical actors, the actor here being states, interact and cooperate successfully. This is an important finding because it carries serious implications for international governance — by medium of the influential contributions of fostering norm-setting in the desired direction. As such, in order to have a real effect on climate change a robust international regime is required.

Regime theory

Regimes in the international system represent a tremendously important feature for governance, particularly so with climate change. By definition, regimes are a set of ‘…implicit or explicit principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures around which actors’ expectations converge in a given area of international relations’ (Krasner, 1982: 185). The only plausible solution to the climate problem is to create an international regime. They are crucial when considering governance of climate change, as will be developed in this article, and they are institutionalised based on agreed actions between actors. Regimes can be agreed by states, government organisations, nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), and civil societies among others. The Paris Agreement is an example of a regime and is a source for understanding the pattern of intergovernmental cooperation that is so fundamentally essential in order to successfully govern climate change.

So, it is possible to suggest that regimes are essential when attempting to overcome the challenge that climate change poses. As discussed, it is a global issue — and cooperation under anarchy is key. Regime theory seeks to understand this, and is a concept that is used to examine the contradiction that the anarchical international system is underpinned by cooperating states even though each state involved is motivated by its own self-interests. It seeks to answer when and how said cooperation between anarchical parties can exist and ‘…to account for how regimes emerge, how they affect state behaviour and why they differ’ (Brown 2014: 372). However, although cooperating through regimes is paramount to the success of new principles, mitigation procedures, adaptation procedures, and compliance measures; they are not without limitations.

When regarding potential weaknesses of regimes, international anarchy can be considered a reason that they develop slowly, or fail entirely. Having no overarching authority in the international system can be a stumbling block to potential cooperation since ‘…states cannot reliably tell what the other states’ intentions are or trust that their partners will honour agreements’ (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, 2014: 56). It goes without saying that this obstacle has hindered progress with the issue of climate change. Without adequate knowledge and assurance about the intentions and progress of partners, a regime has a higher chance of failure. Therefore an effective and robust regime must be transparent enough to reduce uncertainty, supported by accountability mechanisms and compliance agreements in order to increase chances of success.

The Paris Agreement is an example of this success, where the regime has taken into account the aforementioned weaknesses of previous regimes and implemented what ought to be done, how, and followed it up with five-yearly reports. Said reports form ‘…a 5-year ambition cycle and a transparency and accountability system’ (European Commission, 2015). According to Mette Eilstrup-Sangiovanni in Block 4 of Module material; by setting specific rules and guidelines, regimes can provide focal points which ‘…help [actors] coordinate on particular cooperative outcomes’ (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, 2014: 58), increasing the chance of success. As mentioned above, the 197 Parties committing to the Paris Agreement all did so voluntarily. The Agreement successfully facilitated cooperation, in part, by legally binding all states to provide information in order to allow for monitoring and reporting of conformity. Doing so has two advantages; allowing a focal point for the perceived benefits from all actions taking place and also by reducing potential uncertainty of other members.

There are different understandings of regimes depending on whether neorealist or liberal institutionalist lenses are adopted when attempting to understand the how’s and why’s regarding cooperating states under anarchy. These highly significant theoretical understandings, two widely accepted approaches in regime theory, will be explored in some detail below. This is because these approaches allow for an understanding of how successful actors such as civil societies and states have sought the governance of climate change. Both neorealist and liberal institutionalist approaches understand and agree that the international system is governed by ruled activities, yet disagree in other areas. Therefore a theoretical understanding of regimes is strongly desirable, and crucial, as will be revealed, if cooperation under anarchy is to be understood and facilitated effectively.

Neorealism on Regimes

According to Stephen Krasner, the understanding of regime theory ‘…depends on the broader theoretical framework that you embrace’ (The Open University, 2015). With that; regimes are ‘…principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures that are more or less dictated by the most powerful states in the international system’ (The Open University, 2015) when a neorealist approach is embraced. A neorealist would explain that climate governance refers to state power distribution and state interests. They would explain the existence of cooperation in the international system by suggesting that strong state powers, hegemons, act in a supportive nature when funding or implementing international regimes — because it is in their own interest to do so. A weakness with this school of thought is that this behaviour could be perceived as a state-centric, self serving approach that ultimately increases uncertainty and perpetuates a lack of cooperation internationally. With the neorealist position being ‘…dependent upon state interests and power…’ (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, 2014: 57), regimes should consequently lack in quantity and also cooperative ability would be inhibited. Climate governance flies in the face of this position, however, because all states regardless of status and power have a vested interest in the threat of climate change. Where, in the eyes of the neorealist, hegemonic states are central to the implementation and survival of regimes; forms of coordination become necessary to allow ruled activity to take place under anarchy conditions. The neorealist would therefore explain that the form of cooperation that is sought here is primarily one of a coordination of efforts to tackle the threat to security that is climate change. To a neorealist, the cost-to-gain analysis of regime forming becomes an important consideration for a state to continue pursuing power and ensuring its security and survival.

Studying the Paris Agreement through the neorealist way of thinking produces a problematic thought. As realism requires a strong hegemony, what would happen if global powers went into decline? The neorealist would want to know who is in charge, who has the most power. They would say that the diverging interests among the lesser-power states in the international system would increase conflict and reduce cooperation to a point where the regime could become ineffective or ultimately fail. This train of thought applies the same for any regime within the international system, the Kyoto Protocol hints of this also. Global governance of climate change was not possible using the Kyoto regime alone due, in part, to one particular hegemon letting the norm collapse, in this instance the USA (Reynolds, 2001). They did so because it was not in their interest. However, in terms of how successfully actors have sought to govern issues using a neorealist approach; regimes promote coordination between actors, and the actors holding most power have the largest influence because they have the power to enforce cooperation in their own interests.

Under a neorealist approach, wider focus on the Paris Agreement as a product of COP21, during which the central aim was to ‘…strengthen the global response to the threat…’ (UNDESA n.d.), shows that 197 Parties opted to coordinate together to govern climate change as a form of cooperation. This form of cooperation can be considered a success because ‘In coordination… the main difficulty is reaching agreement’ (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, 2014: 65). As a measure of actors attempting governance using a neorealism approach to regimes; the Paris Agreement indicates promising outcomes for governance within the international system. However, because the stakes are so high; this success is merely reinforced by the strength of vested interests since ‘…regimes are seen as dependent upon state interests’ (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, 2014: 57) and all actors seek the mutual benefits of addressing climate change. They must, because non-compliance in the governance of climate change ‘…would leave them materially worse off’ (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, 2014: 63), perhaps irreversibly so because of the threat to power, to humankind, from climate change. So, the neorealist approach supports the thought that all states abide by international regimes only when their self-interest is satisfied, however, liberal institutionalists hold stronger conclusions.

Liberal Institutionalism on Regimes

Because the issue of climate change is global, the solution to it is global and political. Step in liberal institutionalism. The role of institutions, communities, bodies, and rules speak volumes when it comes to success in governance over any particular areas of interest in the international political sphere. According to William Brown in Block 1 of Module material, ‘…liberal institutionalism… refers to a tradition that emphasises the importance of international institutions in fostering cooperation and peace between states’ (Brown, 2014: 115). One of the main themes of this article is the importance of cooperation because this is a measure of success of governance in the international system. International actors will not voluntarily commit to cooperating effectively with the presence of fear and a lack of trust amidst one-another. Working together is the only solution to some of the most concerning issues being dealt with by the international system today. Liberal institutionalism seeks to facilitate this. It is ‘…instrumental therefore in lessening the fear, lack of trust and uncertainty that, for realists, lie at the heart of the insecurity of international politics’ (Brown, 2014: 115). It seeks to facilitate a transparency regarding information between actors and enables the monitoring of one-another’s actions and behaviour, or more specifically, compliance. By encouraging a harmony of interest, subsequent cooperation between states can negate the balance of power, by all partakers, through the sharing of sovereignty. It also negates zero-sum conflicts. These are lofty statements, but under the approach of liberal institutionalism; with cooperation combined with facilitated shared aims and preferences, the balance of power and conflicts become insignificant. According to Brown, ‘The European Union (EU) is often cited as the leading example of this kind of cooperation’ (Brown, 2014: 115).

A potential weakness to liberal institutionalism is that it is necessary for actors to have similar concerns and priorities in order to experience true and enduring harmony. In answer to this; the liberal institutionalist would want to know what needs to be done in order to align preferences and interests to increase cooperation over said concerns and priorities. As Brown suggests; ’…a more cooperative and harmonious world will be achieved when states’ preferences are similar, than when they are deeply divided’ (Brown, 2014: 118). This perceived weakness can be countered by facilitating a negotiating table by means of institutions themselves. This weakness is quashed by the very nature if liberal institutionalism; ‘…by helping to settle distributional conflicts and by assuring states that gains are evenly divided over time, for example by disclosing information … and capacities of alliance members’ (Corry, 2014: 143).

To the liberal institutionalist, regimes enable actors to cooperate in the form of collaboration. They can be used to counter the risk of an actor defecting from a mutual agreement in pursuit of a more favourable individual interest. If the Kyoto Protocol, for example, was effective and well devised using the most optimal solution to promote the common good then the regime may have been a resounding success. If that was case, the Paris Agreement may have been an agreement that looked to shape the post-fossil fuel era of humankind — instead of one that corrected the wrongs of Kyoto by using a more liberal institutionalist approach. This is where liberal institutionalism can hold its head high, since the approach would look to foster an optimal solution to the issue so that the risk of defection by all and any party diminishes, as is looking promising today with the Paris Agreement.

This particular regime has shown that it is possible for actors to successfully seek, establish and maintain global governance in the international system. The Paris Agreement shows this by enabling actors ‘…to continue working together so as to strengthen action, support and ambition, moving from a focus on negotiation to a focus on implementation and cooperation’ (Ségolène, 2016b), with its onus on ‘respecting balance’ throughout. This respecting of balance suggests of an attempt to negate the concern for other actors defecting from the agreement. Liberal institutionalists understand the importance of fostering collaboration and cooperation, therefore any regime under anarchy must include a mechanism to encourage ‘…interdependent patterns of state preferences’ (Brown, 2014: 124). For that reason it is possible to convey that liberal institutionalism favours the emergence of globalisation for climate change, and in the wider focus; global governance in general.

Different actors

Climate governance requires multiple stakeholder contributions with regard to effective regime forming. With that in mind, non-state actors play a key role in the implementation of mitigation and adaptation for climate change. Returning to the point of a slow momentum early on in climate change politics, and the reflection of a lack of global attention due to a lack of scientific agreement, NGOs played a crucial role in improving this. The success of the Paris Agreement goes hand in hand with the actions taken by NGOs. The UNFCCC welcomed NGO participation ‘…to strengthen the knowledge, technologies, practices and efforts of local communities and indigenous peoples, as well as the important role of providing incentives through tools such as domestic policies and carbon pricing’ (UNFCCC n.d. e). Specifically, a non-state actor involved with climate governance, the Non-State Actor Zone for Climate Action (NAZCA) is a global platform which ‘…brings together the commitments to action by companies, cities, subnational regions, investors and civil society organizations to address climate change’ (NAZCA, 2016). The NAZCA was an essential tool for underpinning international support for COP21 and today it continues to ‘…play a key role in the implementation of the Paris Agreement, providing visibility to the diversity of climate action, mobilize broader engagement and accelerate ambition’ (NAZCA, 2016). NGOs attend UNFCCC sessions, provide inputs and the views of outer-NGO delegates in order to offer credible and authoritative assistance. This involvement has enabled important information and expertise from the civil society to be promulgated, proving to be a valuable actor in the governance of climate change. It becomes possible to convey that the success of actors, all and any actors, concerning climate governance depends entirely on cooperation. In resolute agreement with US Secretary of State John Kerry; climate change is ‘…quintessentially global challenge… one that transcends borders, sectors and levels of government’ (BECA, n.d.). As such, with COP21 and the Paris Agreement in mind; these actors have been highly successful in seeking global climate governance.

Conclusion

Climate change has allowed a form of global governance to gain a foothold in the international system. And this is great news. If one particular problem area can facilitate this, climate change is it. The real world implications for the success of climate governance speaks volumes regarding effective and enduring mitigation and adaptation to protect humankind from the threat. Above all, any proposed changes would benefit exponentially if established by regimes supported with the truly future-proof liberal institutionalist approach. To that end; the Paris Agreement is a course of action which shows that when actors cooperate, policy aims and courses of action regarding even the most significant and momentous international issues can be governed successfully.

Bibliography

BECA (n.d.) Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, Our Cities Our Climate [Online]. Available at https://eca.state.gov/ivlp/our-cities-our-climate

Brown, W. (2014) ‘Theoretical reflections: Realism and liberalism’ in Brown, W., Corry, O. and Czajka, A. (eds) International Relations: Continuity and Change in Global Politics 1, Milton Keynes, Open University

Brown, W. (2014) ‘Glossary’ in Brown, W., Corry, O. and Czajka, A. (eds) International Relations: Continuity and Change in Global Politics 1, Milton Keynes, Open University

Corry, O. (2014) ‘Theoretical reflections: liberal institutionalism and global governmentality’ in Brown, W., Corry, O. and Czajka, A. (eds) International Relations: Continuity and Change in Global Politics 2, Milton Keynes, Open University

Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, M. (2014) ‘Weapons proliferation: regimes and networks in international governance’ in Brown, W., Corry, O. and Czajka, A. (eds) International Relations: Continuity and Change in Global Politics 2, Milton Keynes, Open University

EPA. (2016) United States Environmental Protection Agency, Agriculture and Food Supply [Online]. Available at https://www3.epa.gov/climatechange/impacts/agriculture.html

European Commission. (2015) Questions and answers on the Paris Agreement [Online], Brussels, European Commission Climate Negotiations. Available at

http://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/international/negotiations/paris/docs/qa_paris_agreement_en.pdf

Gosden, E. (2015). World leaders pose for a family photo during the COP21 Conference [Online] Available at http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/earth/paris-climate-change-conference/12024206/Paris-climate-change-conference-LIVE-world-leaders-meet-for-UN-talks.html

Griggs, M. (2016) ‘April’s temperatures broke records for the 12th consecutive month’, Popular Science, 18 May 2016 [Online]. Available at http://www.popsci.com/aprils-temperatures-broke-records-for-12th-consecutive-month

IPCC. (2014) Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report [Online], Switzerland, World Meteorological Organization. Available at

http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/syr/SYR_AR5_FINAL_full_wcover.pdf (Accessed 23 May 2016)

NAZCA (2016) Non-State Actor Zone for Climate Action, About NAZCA [Online]. Available at http://climateaction.unfccc.int/about

NBC. (2005) ‘Kyoto: “Bush: Kyoto treaty would have hurt economy”’, NBC News, 30 June 2005 [Online] Available at: http://www.nbcnews.com/id/8422343/ns/politics/t/bush-kyoto-treaty-would-have-hurt-economy/#.VzyrYGOxHzI

Reynolds, P. (2001) Kyoto: ‘Why did the US pull out?’, BBC News, 30 March 2001 [Online] Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/1248757.stm

Santiago, J. (2015) ‘15 quotes on climate change by world leaders’, World Economic Forum, 27 November 2015 [Online]. Available at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/11/15-quotes-on-climate-change-by-world-leaders/

Secretariat. (2013) IPCC Factsheet: What is the IPCC? [Online], Switzerland, World Meteorological Organization. Available at http://www.ipcc.ch/news_and_events/docs/factsheets/FS_what_ipcc.pdf

Ségolène, R. (2016a) Taking the Paris Agreement forward, Reflections note [Online], Report Annex II p. 6, Germany, UNFCCC. Available at http://unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9485.php

Ségolène, R. (2016b) Taking the Paris Agreement forward, Reflections note [Online], Report p. 1, Germany, UNFCCC. Available at http://unfccc.int/files/meetings/paris_nov_2015/application/pdf/reflections_note.pdf

Krasner, S. (1982) ‘Structural causes and regime consequences: regimes as intervening variables’, International Organization, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 185–205.

The Open University (2015) ‘4.1.2. Theory bites video 7: Stephen Krasner’ [Video], DD313 International relations: Continuity and change in global politics. Available at https://learn2.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/olink.php?id=701898&targetdoc=Week+17%3A+Governance+and+regimes&targetptr=5.1.2

UNDESA. (n.d.) United Nations Department of Economics and social affairs, Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform [Online]. Available at https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/frameworks/parisagreement

UNFCCC. (n.d. a) United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Feeling the Heat: Climate Science and the Basis of the Convention [Online]. Available at http://unfccc.int/essential_background/the_science/items/6064.php

UNFCCC. (n.d. b) United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, First steps to a safer future: Introducing The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change [Online]. Available at http://unfccc.int/essential_background/convention/items/6036.php

UNFCCC. (n.d. c) United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Kyoto Protocol [Online]. Available at http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/items/2830.php

UNFCCC. (n.d. d) United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, The Paris Agreement [Online]. Available at http://unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9485.php

UNFCCC. (n.d. e) United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Get The Big Picture [Online]. Available at http://bigpicture.unfccc.int/#content-the-paris-agreemen

Vidal, J. (2015) ‘UK floods and extreme global weather linked to El Niño and climate change’, The Guardian, 27 December 2015 [Online] Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/dec/27/uk-floods-and-extreme-global-weather-linked-to-el-nino-and-climate-change

WBG. (2016) The World Bank Group, Water and Climate Change [Online]. Available at http://water.worldbank.org/topics/water-resources-management/water-and-climate-change

WHO. (2016) World Health Organization, Climate change and health [Online]. Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs266/en/

WMO. (n.d.) World Meteorological Organization, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change [Online]. Available at https://www.wmo.int/pages/themes/climate/international_unfccc.php